FREQUENTLY ASKED QUESTIONS (FAQs) |

* Question: Who is a Hindu?

* Question: Why is the symbol of “Swastika” used in Hindu tradition?

* Question: What is that red dot on the forehead of Hindu ladies?

* Question: Why do we light a lamp?

* Question: Why do we blow a conch?

* Question: What are the colored designs at the front entrance of homes?

* Question: What is the significance of the “saffron” color in Hindu tradition?

* Question: What is the importance of Lotus in Hindu Tradition?

* Question: Why is “kalasha” (pitcher) used in Hindu worship?

* Question: Namaste – How we greet?

* Question: What do Hindus regard as their major duties? - Five Great Duties

* Question: What is a Mahāvākya?

Question: Who is a Hindu?

The simplest and most common answer is: A person born into a Hindu family, with at least one Hindu parent, is a Hindu. Most Hindus, both practicing as well as non-practicing, will qualify as Hindus under this definition.

Obviously, this definition would not cover the growing number of persons who, born into non-Hindu families, have come to accept and practice the Hindu beliefs on their own.

A more meaningful definition, therefore, may be that a person who lives by Hindu principles, celebrates some Hindu festivals, and observes some of the Hindu traditions as being part of a community. This might include some of the following:

- Celebrating some sacraments (samskaar) like upanayan, marriage, death ceremonies, etc. in Hindu way;

- Celebrating some festivals, like Holi, Diwali, Janmasthami, Navratri, etc.; and

- Participating in some of the general community practices like temple worship, etc.

Some higher level criteria may include such characteristics as having worthwhile objectives (purushaartha) in life, belief in the philosophy of Karma, belief in rebirth and evolution of the soul, and working towards liberation from the cycles of birth and death or samsaara (moksha).

A more formal definition, based on the Criteria of Scriptural Authority, would define a Hindu as an individual who accepts as authoritative the religious guidance of the Vedic scriptures and who strives to live in accordance with Dharma as revealed in the Vedic scriptures.

In keeping with this definition, all of the Hindu thinkers of the six traditional schools of Hindu philosophy (Shad-darshanas) insisted on the acceptance of the scriptural authority of the Vedas (shabda-pramana) as the primary criterion for distinguishing a Hindu from a non-Hindu, as well as distinguishing overtly Hindu philosophical positions from non-Hindu ones. If you accept the Vedas (and by extension Upanishadas Bhagavad Gītā, Purānas, epics, etc.) as your scriptural authority, and live your life in accordance with the Dhārmic principles of the Vedas, you are a Hindu. Thus, an Indian who rejects the Veda is obviously not a Hindu, while an American, Russian, Indonesian, or an Indian who does accept the Vedas, is a Hindu.

It has also been argued that Hinduism is really the Sanātan Dharma or the Eternal Way of Existence and is not really a religion. That is the reason that there are no requirements to adhere to specific rituals to be a Hindu.

Please note that all definitions carry an element of truth; though some definitions are more comprehensive than the others. Therefore, regardless of which definition you use, be proud that you are a Hindu. Be grateful that, while you respect all religions and religious traditions, as a Hindu you have the total freedom to choose your own path of worship.

QUESTION: Why is the symbol of “Swastika” used in Hindu tradition?

Second in importance only to the OM, the Swastika symbol holds a great religious significance for the Hindus. The same would appear to be the case for Jains and Buddhists.

Unlike OM, Swastika is not a syllable or a letter, but a pictorial representation in the shape of a cross with branches bent at right angles and facing in a clockwise direction. A must for most religious celebrations and festivals, Swastika symbolizes the eternal nature of the Brahman, for it points in all directions, thus representing the omnipresence of the Absolute.

The term 'Swastika' is a fusion of the two Sanskrit words 'Su' (good) and 'Asati' (to exist), which, when combined, means May good prevail!.

Unlike OM, Swastika is not a syllable or a letter, but a pictorial representation in the shape of a cross with branches bent at right angles and facing in a clockwise direction. A must for most religious celebrations and festivals, Swastika symbolizes the eternal nature of the Brahman, for it points in all directions, thus representing the omnipresence of the Absolute.

The term 'Swastika' is a fusion of the two Sanskrit words 'Su' (good) and 'Asati' (to exist), which, when combined, means May good prevail!.

History of Swastika

Like OM, the origin of Swastika is lost in the misty past and it can only be guessed by piecing together of the surviving clues. Some historians believe that, in ancient times, forts were often built in the shape of a grid closely resembling the Swastika for defense reasons. Such design made it difficult for an enemy to storm into all parts of the fort simultaneously. For its protective power, this shape began to be sanctified.

Another explanation traces its history to the beginning of our earth and the solar system. It is believed that there was an explosion and scattering of energy in all directions (Scientists call this explosion the Big Bang). As a result, our earth and other planets formed. The energy scattered in all directions as symbolized by the shape of Swastika.

In the Hindu tradition, Swastika has been used as a symbol of Sun or Vishnu. It is a solar symbol, spreading out light and energy in all four directions. It symbolizes cosmos and the progress of the Sun through space. The four arms of Swastika stand for four main directions: North, South, East, and West. It also derives its auspiciousness from the four-fold principles of divinity:

- Brahma is said to be four-faced.

- Four Vedas, namely, Rig, Sama, Yajur and Atharva;

- Four Ashramas (four stages of life), namely, brahmacharya (celibacy), grihastha (house-holder), vana-prashta (seclusion), and sanyasa (renunciation).

- Four Varnas, namely, Brahman, Kshatriya, Vaishya, and Shudra.

- Four Purushaarthas (aims of life), namely, Dharma (righteousness), Artha (acquiring wealth); Kama (fulfilling desires); and Moksha (libe-ration from the earthly life cycles).

Swastika also represents the world-wheel, the eternally changing world, round a fixed and unchanging center, God.

In Hinduism, it is also regarded as a symbol of Lord Ganesha and is often displayed along with the symbols of the Navagrahas (nine pl anets). Since ancient times, Hindus have used this symbol on all auspicious occasions, including all social, cultural, and religious ceremonies. For every holy occasion, Swastika symbol is drawn, painted, carved, or sculpted at the place of worship. To signify birth, marriage, or any joyous occasion, Rangoli of swastika forms constitute essential decoration. Swastika indicates happiness, safety, fertility, and prosperity.

Swastika is to be seen everywhere across the Indian sub-continent: sculptured into temples both ancient and modern, decorating buildings, houses, shops, painted onto public buses, in taxis -- even decorating the dashboards of the three-wheeler motor rickshaws. It is probably the most prevalent symbol one will see in India. Every Hindu respects the symbol of prosperity and well-being.

[Please note: In 1935, the black swastika on a white circle with a crimson background became the national symbol of Germany. The Nazis took the ancient symbol, erased the good meaning of the swastika, the symbol of purity and of life. It was certainly a misuse of the sacred symbol which is supposed to promote the well being of all. Also, unlike the ancient swastika symbol, which is rested flat, the Nazi swastika is at a slant. So, don’t confuse the Nazi symbol of hate with sacred ancient symbol of well being.]

Question: What is that red dot on the forehead of Hindu ladies?

It is called “bindi”. Bindi is usually a small or a big eye-catching round mark made on the forehead of Hindu women as adornment. It is also referred to by other names, such as 'tika', 'pottu', 'sindoor', 'tilak', 'tilakam', and 'kumkum'

Although most girls can wear a bindi, it is the prerogative of the married woman. A red dot on the forehead is an auspicious sign of marriage and guarantees the social status and sanctity of the institution of marriage. The Indian bride steps over the threshold of her husband's home, bedecked in glittering apparels and ornaments, dazzling the red bindi on her forehead that is believed to usher in prosperity, and grants her a place as the guardian of the family's welfare and progeny.

Significantly, when an Indian woman has the misfortune of becoming a widow, she stops wearing the bindi. Also, if there is death in the family, the women folks' bindi-less face tells the community that the family is in mourning.

Hindus attach great importance to this ornamental mark on the forehead between the two eyebrows -- a spot considered a major nerve point in human body since ancient times.

The area between the eyebrows, the sixth chakra known as the 'agna' meaning 'command', is the seat of concealed wisdom. It is the center point wherein all experience is gathered in total concentration. During meditation,. latent energy rises from the base of the spine towards the head. The red 'kumkum' between the eyebrows is said to retain energy in the human body and control the various levels of concentration. It is also the central point of the base of the creation itself -- symbolizing auspiciousness and good fortune.

The term 'bindi' is derived from the Sanskrit word 'bindu' or a drop, and suggests the mystic third eye of a person. The vermilion, traditionally used exclusively for bindis, is called 'sindoor'. It means 'red', and represents Shakti (strength). It also symbolizes love -- one on the beloved's forehead lights up her face and captivates the lover. As a good omen, 'sindoor' is placed in temples or during celebrations along with turmeric (yellow) that stands for intellect.

How to Apply Bindi

Traditional bindi is red or maroon in color. A pinch of vermilion powder applied skillfully with practiced fingertip make the perfect red dot. Women, who are not nimble-fingered, take great pains to get the perfect round. They use small circular discs or hollow pie coin as aid. First they apply a sticky wax paste on the empty space in the disc. This is then covered with kumkum or vermilion a

nd then the disc is removed to get a perfect round bindi.

Sindoor in Scriptures

'Sindoor' and 'kumkum' are of special significance on special occasions. The practice of using 'kumkum' on foreheads is mentioned in many ancient texts (Puranas), including Lalitha Sahasranamam and Soundarya Lahhari. Legends have it that Radha turned her 'kumkum' bindi into a flame-like design on her forehead. In Mahabharata, Draupadi wiped her 'kumkum' off the forehead in despair and disillusion at Hastinapur.

Bindi as a Fashion Statement

Nowadays, with changing fashion, women try out all sorts of shapes and designs. It is, at times a straight vertical line or an oval, a triangle or miniature artistry made with a fine-tipped stick, dusted with gold and silver powder, studded with beads and crusted with glittering stones. The advent of the "sticker-bindi", made of felt with glue on one side, has not only added colors, shapes and sizes to the bindi but is an ingenious easy-to-use alternative to the powder. Today, bindi is more of a fashion statement than anything else, and the number of young performers sporting bindis is overwhelming, even in the West.

Men usually have Tilak or Tikka which is a mark of red powder or sandalwood paste that is applied on the forehead of a person mostly before prayers. In the vaishnava tradition, the sandalwood paste is applied all over the forehead showing three vertical lines representing threesome nature of God, namely, Brahma, Vishnu and Mahesha representing creation, preservation and destruction, respectively. In the Shavaite tradition, the lines marked are horizontal. The forehead is considered a seat of memory and the 'spiritual eye or the third eye'. Sandalwood is used as it has cooling properties and a very pleasant aroma. This signifies that one's head should remain calm and should generate pleasant thoughts. Tilak is also applied at the forehead for good luck or good wishes on special occasions.

Source: MARG, Jan-Feb 2006, 3#1, p.27.

QUESTION: Why do we light a lamp?

In almost every Indian home a lamp is lit daily before the altar of the Lord. In some houses it is lit at dawn, in some, twice a day - at dawn and dusk - and in a few it is maintained continuously (akhanda deepa). All auspicious functions commence with the lighting of the lamp, which is often maintained right through the occasion. It is customary to light a lamp at the beginning of most conferences, cultural programs, and similar activities and celebrations.

Light symbolizes knowledge, and darkness, ignorance. The Lord is the "Knowledge Principle" (chaitanya) who is the source, the enlivener and the illuminator of all knowledge. Hence light is worshiped as the Lord himself.

Light symbolizes knowledge, and darkness, ignorance. The Lord is the "Knowledge Principle" (chaitanya) who is the source, the enlivener and the illuminator of all knowledge. Hence light is worshiped as the Lord himself.

Knowledge removes ignorance just as light removes darkness. Also knowledge is a lasting inner wealth by which all outer achievement can be accomplished. Hence we light the lamp to bow down to knowledge as the greatest of all forms of wealth

Why not light a bulb or tube light? That too would remove darkness. But the traditional oil lamp has a further spiritual significance. The oil or ghee in the lamp symbolizes our vaasanas or negative tendencies and the wick, the ego. When lit by spiritual knowledge, the vaasanas get slowly exhausted and the ego too finally perishes. The flame of a lamp always burns upwards. Similarly we should acquire such' knowledge as to take us towards higher ideals.

While lighting the lamp, we thus pray:

Deepajyoti parabrahma

Deepa sarva tamopahaha

Deepena saadhyate saram

Sandhyaa deepo namostute

[I prostrate to the dawn/dusk lamp; whose light is the Knowledge Principle (the Supreme Lord), which removes the darkness of ignorance and by which all can be achieved in life.]

Source: MARG, Nov-Dec ’07, 3#6, p.19.

Question: Why do we blow a conch?

When the conch is blown, the primordial sound of Om emanates. Om is an auspicious sound that was chanted by the Lord before creating the world. It represents the world and the Truth behind it.

The legend has it that the demon Shankhasura defeated devas, and took the Vedas to the bottom of the ocean. Devas appealed to Lord Vishnu for help. He incarnated as Matsya Avataara – the "fish incarnation", and killed Shankhasura. The Lord then blew the conch-shaped-bone of his ear and head to produce the sound of Om from which emerged the Vedas.

All knowledge enshrined in the Vedas is an elaboration of Om. The conch therefore is known as shankha after Shankasura. The conch blown by the Lord is called Panchajanya. He carries it at all times in one of His four hands. It represents dharma or-righteousness that is one of-the four goals (purushārthas) of life. The sound of the conch is thus also the victory call of good over evil.

Another well-known purpose of blowing the conch is to drown or mask the negative noises or sounds that may disturb or upset the atmosphere or the minds of devotees.

Ancient India lived in her villages. Each village was presided over by a primary temple and several small ones. During the aarati performed after all-important poojas and on sacred occasions, the conch used to be blown. Since villages were generally small, the sound of the conch would be heard all over the village. People who could not make it to the temple were reminded to stop whatever they were doing, at least for a few seconds, and mentally bow to the Lord. The conch sound served to briefly elevate people's minds to a prayerful attitude even in the middle of their busy-daily routine.

The conch is also placed at the altar in temples and homes next to the Lord. It is often used to offer devotees sanctified water to raise their minds to the highest Truth. The warriors of ancient India blew conches to announce battle, such as at the start of the war of Mahābhārata.

Source: MARG, Nov-Dec ’07, 3#6, p.19.

QUESTION: What are the colored designs at the front entrance of homes?

These designs are called “Rangoli”. Rangoli is one of the most popular art forms in India. It is a form of decoration that uses finely ground white powder and colors, and is used commonly outside homes in India. Rangoli can be wall art as well as floor art.

The term “rangoli” is made up of two words, rang (color) and avali, meaning row of colors, or creepers of colors. Rangoli is known by different names in different parts of the country:

The term “rangoli” is made up of two words, rang (color) and avali, meaning row of colors, or creepers of colors. Rangoli is known by different names in different parts of the country:

- Aalpana in Bengal,

- Aripana in Bihar,

- Madana in Rajasthan,

- Rangoli in Gujarat, Karnataka, and Maharashtra,

- Chowkpurana in Uttar Pradesh,

- Kolam in Kerala, and Tamilnadu, and

- Muggu in Andhra-pradesh.

Some of these, especially many of the North Indian ones, like Aalpana, more often refer to floor painting with traditional wet color, rather than the powder rangoli more conventional in south India. The patterns are made with rice powder, crushed lime stone, or colored chalk. They may be topped with grains, pulses, beads, or flowers. In the deep South and South West of India and Kerala, flowers are used to create floor art.

Rangoli designs are passed down from generation to generation, with some of them being hundreds of years old. Though the design vary in different sections of India, the basic methodology is common in all areas. The designs are usually geometric and symmetrical, while some nature elements like flowers and birds may be imported. Though making of a Rangoli is highly dependent on the preferences and skills of the maker, lines are always drawn with one finger movement (rangolis are always drawn with fingers) and frequently, the mapping of the rangoli is done with the help of dots, which are joined to form a pattern, and then the pattern is filled with colors.

Although originally Rangoli was done in small patterns, about 2 feet square, it can be of any size, from the size of a doormat, to the covering an entire room.

The motifs in traditional Rangoli are usually taken from Nature - peacocks, swans, mango, flowers, creepers, etc. The colors are derived from natural dyes - from barks of trees, leaves, indigo, etc. However, today, synthetic dyes are also used in a range of bright colors. The designs are symbolic and common to the entire country, and can include geometrical patterns, with lines, dots, squares, circles, triangles; the swastika, lotus, trident, fish, conch shell, footprints (supposed to be that of goddess Lakshmi), creepers, leaves, trees, flowers, animals, and anthropomorphic figures. These motifs often are modified to fit in with the local images and rhythms. One important point is that the entire pattern must be an unbroken line, with no gaps to be left anywhere for the evil spirit to enter.

The whole object of making rangoli at Diwali time is to welcome Goddess Lakshmi, the Goddess of wealth, to individual homes. Thus small footprints coming into the home, representing the footprints of the Godess L:akshmi, are also made. In fact, in Indian tradition, all guests and visitors are regarded as manifestation of divinity [Atithee devo bhav] and occupy a very special place. Rangoli, as an expression of the warm hospitality, welcomes all guests.c

Like Hindu and Buddhist Mandalas, the reason for using powder or sand as a medium for creating Rangoli (and its resulting fragility) is sometimes thought to be a metaphor for the impermanence of life and maya.

Traditionally, such floor decorations were done only on auspicious occasions or festivals. But these days, any occasion is good enough -- weddings, birthday parties, inaugural ceremonies, etc. Rangoli also has a religious significance, invoking the holy spirit of the deities, enhancing the beauty of the surroundings, and spreading joy and happiness all around.

Rangoli also makes a good introduction for the children to learn Indian art, Hindu symbols and icons, and aspects of Indian culture. They should start with simpler designs and, with the help of their older friends and parents, progress to more complex and elaborate design, use of different kinds of rangoli materials, and color coordination. It is both a lot of fun and good learning!

Source: MARG, Sep-Oct ’08, 2$5, p. 28.

QUESTION: What is the significance of the “saffron” color in Hindu tradition?

The saffron color is considered auspicious by Hindus. This color is most prominently visible in their flag, robes worn by holy persons, and the tilak (sacred mark applied on the forehead). Statues of Hindu Gods are often daubed with saffron paste. If there is any color that can symbolize all aspects of Hinduism, it’s saffron – the color of Agni, or, fire and its flames.

The fire is the great purifier and, in Hindu tradition, all sacrifices are offered to the fire. It stands for the principle of sacrifice. Saffron is also the color of sunrise and sunset. When the day dawns, the rising sun reminds us to wake up, shake off lethargy, and do our duty. The sun burns throughout the day giving life to one and all without demanding anything in return. The sunset teaches us the true principle of giving by serving the society without any expectation.

The fire is the great purifier and, in Hindu tradition, all sacrifices are offered to the fire. It stands for the principle of sacrifice. Saffron is also the color of sunrise and sunset. When the day dawns, the rising sun reminds us to wake up, shake off lethargy, and do our duty. The sun burns throughout the day giving life to one and all without demanding anything in return. The sunset teaches us the true principle of giving by serving the society without any expectation.

The saffron color, thus, is a symbol of renunciation and depicts the spirit of selfless service. In the diverse and multi-faceted Hindu religion, it is one of the few elements which command a universal respect and acceptance among -all Hindus.

Origin of the Acceptance of Saffron Color

The origin of the acceptance of saffron color as an auspicious color lies in the hazy past. Fire worship had its origin in the Vedic age. When sages moved from one ashram to another, they often carried fire with them. Later, the inconvenience of carrying a burning substance over long distances might have given rise to the symbol of a saffron flag, triangular in shape and often forked, depicting rising flames. Saffron flags are often seen fluttering atop most Sikh gurudwaras and Hindu temples.

The saffron pigment is traditionally derived from the saffron plant (Autumn crocus) which is called kesar. Thus one of the names of the saffron color is kesri from the plant Kesar. This plant is grown in the sub-Himalayan regions and is very rare. This rarity could have been one of the reasons for this particular color to be highly valued. Another explanation offered is its golden hue. That the golden color of the precious yellow metal had a special status, apart from the high monetary value attached to it, is evident from the term Suvarna that is used to describe it. “Su” is good and “varna” is color; so “suvarna” means the good color.

Among other words used to describe the saffron color are Bhagwa and Naranga. The term Bhagwa could have been derived from the word Bhagwan, meaning God, to identify this color as the one associated with God. Incidentally, Bhagwa in Sanskrit is also used for good fortune, which reaffirms the auspicious significance attached to this color.

The forked triangular saffron flag of the Hindus, having the shape of rising flames from ‘Yagna’, is also known as “Bhagwa Dhwaj” (Dhawaj means Flag). It should be noted here that the Bhagwa Dhwaj is honored as Guru (spiritual teacher) by the members of the Rashtriya Swayamsevak Sangh (RSS), a premier national voluntary organization of Hindus.

Besides Hindus, the saffron color is also auspicious to the Sikhs, the Buddhists, and the Jains. While the Sikhs regard it as a militant color and a symbol of fight against injustice and oppression, Buddhist monks, Jain munies (holy men), and Hindu saints wear robes of this color as a mark of renunciation of material life.

The fact that the saffron color is regarded as sacred even by the Buddhist, Jain, and Sikh religions, indicates that this color must have obtained a religious significance before these religions came into being. No wonder that the Saffron color has always been accorded a place of high honor and esteem by the Hindus in all ages.

So, the next time you see saffron color; don’t think of it just another color. Instead, see it as representative of Hindu history, reflecting Hindu traditions, Hindu thought and philosophy, and Hindu values . . . and be proud of it!

Source: MARG, Jan-Feb ’07, 3#1, p 8.

Question: What is the importance of Lotus in Hindu Tradition?

Hindus use flowers in puja (worship). Though any available flower is auspicious for puja, the most revered and esteemed by God and man is the magnificent lotus.

Hindus use flowers in puja (worship). Though any available flower is auspicious for puja, the most revered and esteemed by God and man is the magnificent lotus.

Hindus have always considered lotus highly sacred. It is given profound significance in epics, scriptures, Sanskrit literature, and historical records. It is the prevailing motif in sculptures, temple carvings, architecture, paintings, and cave murals. Numerous references to the lotus can be found in the Vedas, Upanishads, Puranas, shlokas, and other ancient Sanskrit literature. The most common Sanskrit names for lotus are Kamala, Padma, and Pankaja.

The lotus is the foremost symbol of beauty, prosperity, and fertility. It is the symbol of truth, auspiciousness, and beauty -- satyam, shivam, sundaram. The various aspects of the Supreme are often compared to a lotus, for example, lotus eyes, lotus feet, lotus hands, the lotus of the heart, etc. Hindus believe that, within each human, inhabiting the earth, is the spirit of the sacred lotus. It represents eternity, purity, and divinity and is widely used as a symbol of life, fertility, ever renewing youth and to describe feminine beauty, especially the eyes.

The lotus blooms with the rising sun and close at night. Similarly, our minds open up and expand with the light of knowledge. The lotus grows even in slushy areas. It remains beautiful and untainted despite its surroundings, reminding us that we too can and should strive to remain pure and beautiful within, under all circumstances.

Even though the lotus lead is always in water, it never gets wet. It symbolizes the man of wisdom who remains ever joyous but unaffected by the world of sorrow and change. Bhagavad Gītā compares such a person to lotus who works without attachment, dedicating his actions to God and is untouched by sin like water, as the lotus leaf stands high above the mud and water.

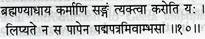

Brahmanyādhāya karmāni Sangam tyaktvā karoti yaha

Lipyate na sa paapena Padma patra mivāmbhasā

-Gītā, 5:10

He, who does actions, offering them to Brahman, abandoning attachment,

is not tainted by sin, just as a lotus leaf remains unaffected by the water on it.

From this, we learn that what is natural to the man of wisdom becomes a discipline to be practiced by all saadhakas or spiritual seekers and devotees.

Our bodies have certain energy centers described in the Yoga Shaastras as chakras. Each one is associated with lotus that has a certain number of petals. In the postures of hatha yoga, the lotus position, padmasana, is adopted by those striving to reach the highest level of consciousness. For example, a lotus with a thousand petals represents the Sahasra chakra at the top of the head, which opens when the yogi attains Godhood or Realization. Also, the lotus posture (padmaasana) is recommended when one sits for meditation. A lotus emerged from the navel of Lord Vishnu. Lord Brahma originated from it to create the world. Hence, the lotus symbolizes the link between the creator and the supreme Cause.

For Buddhists, lotus symbolizes the most exalted state of man--his head held high, pure and undefiled in the sun, his feet rooted in the world of experience. Lord Buddha is said to have been born on a lotus leaf, and the lotus followed the spread of Buddhism to China and Japan.

Lakshmi, Goddess of wealth and good fortune, sits on a fully bloomed pink lotus as Her divine seat and holds a lotus in Her right hand

Lotus blossoms are offered in worship of Lakshmi during Diwali; to Durga in Durgapuja, and to Lord Shiva during Mahasivaratri. The offering of lotus blooms to the Gods is also depicted through traditional mudras, hand gestures, in the introductory steps of classical Bharata Natyam, as well as other forms of Indian dance. The auspicious sign of the swastika is said to have evolved from the lotus.

Source: MARG, Sep-Oct ’07, 3#5, p. 13

QUESTION: Why is “kalasha” (pitcher) used in Hindu worship

A kalasha is brass, clay, or copper pitcher filled with water. Mango leaves are placed in the mouth of the pot and a coconut is placed over it. A red or white thread is tied around its neck or sometimes all around it in a intricate diamond-shaped pattern. The pot may be decorated with designs, such as swstika. Such a pot is known as a kalasha.

A kalasha is brass, clay, or copper pitcher filled with water. Mango leaves are placed in the mouth of the pot and a coconut is placed over it. A red or white thread is tied around its neck or sometimes all around it in a intricate diamond-shaped pattern. The pot may be decorated with designs, such as swstika. Such a pot is known as a kalasha.

When the pot is filled with water or rice, it is known as “purnakumbha” representing the inert body which, when filled with the divine life force, gains the power to do all the wonderful things that makes life what it is.

A kalasha is placed with due rituals on all-important occasions, like the traditional house warming (graha-pravesha), wedding, daily worship, etc. It is placed near the entrance as a sign of welcome. It is also used in a traditional manner while receiving holy personages.

Kalasha is used in puja. The belief is that the water in the kalasha symbolizes the primordial water from which the entire creation emerged. It is the giver of life to all and has the potential of creating innumerable names and forms, the inert objects and the sentient beings, and all that is auspicious in the world from the energy behind the universe. The leaves and coconut represent creation.

The thread represents the love that "binds" all in creation. The kalasha is therefore considered auspicious and becomes an integral part of puja. The waters from all the holy rivers, the knowledge of all the Vedas, and the blessings of all the deities are invoked in the kalasha. Thereafter the kalash water is used for all the rituals, including the abhisheka.

The consecration (kumbha-abhisheka) of a temple is done in a grand manner with elaborate rituals including the pouring of one or more kalashas of holy water on the top of the temple. Legend is that when the asuras (demons) and devatas churned the milky ocean, the Lord appeared bearing the pot of nectar which blessed devatas with everlasting life.

Thus the kalasha also symbolizes immortality. Men of wisdom are full and complete as they identify with the infinite Truth (poornatvam). They brim with joy and love and respect all that is auspicious. We greet them with a purnakumbha ("full pot") acknowl-edging their greatness and, as a sign of respectful and reverential welcome, with a "full heart".

Source: MARG, Sep-Oct ’07, 3#5, p. 14.

QUESTION: Namaste – How we greet?

The traditional greeting of choice in India is “Namaste”. It is used both as greeting as well as on parting. Commonly written "Namaste", it is pronounced as "Namastay" with the two a's as the first “a” in "America" and the “ay” as in "stay", but with the “t” pronounced soft with the area just behind the tip of the tongue pressing against the upper-front teeth with no air passing.

The gesture (or mudra) of namaste is a simple act made by bringing together both palms of the hands before the heart, and slightly and gently bowing the head as one says, "Namaste”. In the simplest of terms, it is accepted as a humble greeting straight from the heart and reciprocated accordingly. The hands held in union signify the oneness of an apparently dual cosmos, the bringing together of spirit and matter, or the self meeting the Self. It has been said that the right hand represents the higher nature or that which is divine in us, while the left hand represents the lower, worldly nature.

The gesture (or mudra) of namaste is a simple act made by bringing together both palms of the hands before the heart, and slightly and gently bowing the head as one says, "Namaste”. In the simplest of terms, it is accepted as a humble greeting straight from the heart and reciprocated accordingly. The hands held in union signify the oneness of an apparently dual cosmos, the bringing together of spirit and matter, or the self meeting the Self. It has been said that the right hand represents the higher nature or that which is divine in us, while the left hand represents the lower, worldly nature.

Namaste is a composite of the two Sanskrit words, nama and te. Te means you, and nama has the following connotations:

- bow,

- obeisance,

- reverential salutation, and

- bending.

Thus, "namaste" literally means "I bow unto you."

The gesture of Namaste represents the belief that there is a Divine spark within each of us. As such, namaste is usually interpreted to reflect the following sentiment as an acknowledgment of the soul in one by the soul in another:

- The God in me greets the God in you.

- The Spirit in me meets the same Spirit in you.

- I honor the Spirit in you which is also in me.

This, of course, is also a way of saying: I recognize that we are all equal. In other words, the act of namaste recognizes the equality of all, and pays honor to the sacredness of all.

The whole action of namaste unfolds itself at three levels:

It starts with a mental submission. This submission is in the spirit of total surrender of the self. This is parallel to the devotion one expresses before a chosen deity, also known as bhakti. To perform namaste, we place the hands together at the heart charka, close the eyes, and bow the head. In another variation, it can also be done by placing the hands together in front of the third eye, bowing the head, and then slowly bringing the hands down to the heart. This is an especially deep form of respect. Although the word "Namaste" is usually spoken in conjunction with the gesture, it is understood that the gesture itself signifies Namaste, and therefore, it is, often, unnecessary to say the word namaste while bowing.

Namaste as a Yoga

As much as yoga is an exercise to bring all levels of our existence, including the physical and intellectual, in complete harmony with the rhythms of nature, the gesture of namaste is yoga in itself. Thus, it is not surprising that any yogic activity begins with the performance of this deeply spiritual gesture.

Meditation depends upon the relationship between the hands (mudras), the mouth (mantras) and the mind (yoga). The performance of namaste is comprised of all these three activities. Thus, namaste is, in essence, equivalent to meditation, which is the language of our spirit in conversation with god, and the perfect vehicle for bathing us in the river of divine pleasure.

It should be noted that, while “Namaste” is and remain the traditional greeting of choice and is very deeply associated with image and culture of India, it is by no means the only form of greeting. There are a large number of other forms of greetings in use throughout India. Often, these greetings reflect one’s religious orientation. Thus, if you’re a devotee of Lord Ram, you might use one of the following phrases for greetings:

- Jai Shri Ram

- Jai Sita Ram; or

- Jai Ram-jee kee.

Devotees of Lord Krishna, particularly if they are members of ISKCON, are more likely to greet you with “Hare Krishna”, or Jai Radha Krishna, or Jai Krishna-Baldev. Another common form of greetings is “Hari Om”. (It is, probably, the greeting of choice in Chinmaya Mission.)

Most Sikhs use the greeting: “Sat Sri Akal” For most Muslim, the greeting of choice is “Salam or Salam-a-Lakim” to be acknowledged with a counter greeting of “Wa-Lakim-Salam”. Another form of greeting, particularly with Urdu speaking population, is: “Adāb-Arz”. The parting greeting in this case might be: “Khudā Hāfiz”, meaning, May God protect you!

Another form of greetings, commonly used in political circles, is “Jai Hind” (Victory to India). It is usually used by a speaker to greet the audience before and after a public speech or address – much like “God bless America”. It is probably a substitute for “Vande Matram” (I bow to Mother India) which was, often, a war cry in the struggle for the independence of India from the British Empire.

Regardless of what form of greetings you use, remember that greeting is an act of recognition and friendship. The act of greeting recognizes the equality of all, and pays honor to the sacredness of all. Naturally, a little smile and humility goes a long way. In the mean time and until we meet again,

Namaste!

Source: MARG, Jan-Feb ’06, 2#1, p. 17-18.

QUESTION: What do Hindus regard as their major duties? - Five Great Duties

The five great duties in the Hindu tradition are defined by “Pancha Mahayajns”. The Sanskrit word “yajna” is derived from the root “yaj” that has three meanings: (a) prayer to God, (b) collective action, and (c) selfless service. Deeds performed with this triple attitude are called Yajna. The word “Panch” means five and “Maha” means great. Hindu scriptures, such as the Vedas, Shatpath Brahman, Laghu Vishnu Smriti, Manu Sniriti, Mahābhārata, and many other sources, identify five great duties (Panch Mahayajna) to be performed in daily life. These were designed to remind people of their obligations towards their environment and nature, ancestors and elders, society and nation, and the animal life. They are not merely religious rituals but are social and moral obligations which, over many centuries, have become deeply ingrained into the Hindu way of life.

The idea of Pancha Mahayajna has influenced many Hindu traditions. Its principles are still followed, knowingly or unknowingly, by Hindus in their daily life, even by those Hindus who do not strictly adhere to religious practices.

These Panch Mahayajna or five great duties are:

- Brahma Yajna (For Knowledge)

- Deva Yajna (For Nature)

- Pitri Yajna (For Ancestors)

- Atithi Yajna (For Society)

- Bhoota Yajna (For Animals)

A brief description of each of the five great duties and their relevance to daily life follows.

Brahma Yajna (For Knowledge)

Brahma Yajna has two main aspects: prayer and study. Brahman is a name given to the creative function of God and creative power (Shakti) is identified as knowledge. Therefore, prayer to God and gaining knowledge are both considered as a daily duty. Hindu scriptures state: “Self-study is Brahmayajna”. (Manu Smriti, 3-70)

In modern life, different types of knowledge are gained from different sources for specific purposes. In this context, the Hindu view of Brahma Yajna can be summarized as follows:

Studying at an educational institute, gaining knowledge about the created world, individual study of the scriptures, and finally praying and meditation, are all aspects of Brahma Yajna in the daily life of a Hindu.

Deva Yajna (For Nature)

Deva Yajna specifies the protection of the environment as a religious duty. The word “Deva” means the one who gives or the one on whom we depend. The givers (Devas) are considered to be the elements of nature. Hindus perform Agnihotra or Havana to maintain purity of atmosphere and environment. Some people wrongly interpret Agnihotra as worship of fire. In fact, it is very similar to a scientific process of fumigation, chemical disinfecting, and sterilization in which camphor and aromatic substances are burnt to purify the environment. Hindu scriptures emphasize this as a religious duty.

Pitri Yajna (For Ancestors)

Pitri Yajna arc deeds performed to fulfill one's obligations towards one's forefathers. Three categories of ancestors are recognized: those with direct hereditary and ancestral links (blood relations); mentors with educational and moral links (gurus, scriptures writers, Rishis); and those with national and cultural links (national leaders who have promoted Dharma). Pitri Yajna has two aspects: Shradha and Tarpana. The word “Shradha” means to offer respect. Respect is offered to living parents. Some Hindu families give to charities on the death anniversary of forefathers. Others show respect to their departed mentors or gurus by inviting learned scholars to their homes and by offering them food. "Tarpana” means to please.

Atithi Yajna (For Society)

An atithi is a person who can arrive at any time without giving notice of the date (tithi) of arrival. According to the Varnashrama system it is the duty of householders to help others, particularly those who were still in student life or those who had renounced the world. Traditionally, the holy men, Sadhus and Sanyasis, roamed around preaching. Their arrival was usually unexpected and householders were required to provide shelter and food for them. Hindu scripture states:

He who eats before sewing the guests destroys the fame and glory of the house.

This tradition of hospitality and service to learned people and visitors is still very strong in Hindu families.

Bhoota Yajna (For Animals)

The word “Bhoota” means one that has life. Bhoota Yajna, also known as Balivaishvadeva Yajna, which is the name given to all charitable deeds done for the poor, the sick, and the animals. Traditionally, Hindus remind themselves of this duly by setting aside five small portions of their food before eating. The scriptures specify the five beneficiaries as:

-

Domestic animals, such as cows and dogs, and wild animals, such as snakes and rats.

- The poor, the homeless and the destitute.

- The sick.

- The birds.

- Insects, such as ants and bees.

The Hindu view is that humans are the greatest of all living beings and their greatness should be reflected in doing good to all other living beings. Hindus believe that animals have soul in the same way as humans do, and that is why vegetarianism is popular among Hindus. The protection of animals is an old Hindu tradition.

Source: MARG, Jan-Feb ’07, 3#1, p 7.

QUESTION: What is a Mahāvākya?

The Mahāvākyas, "the great sentences or sayings" of the Upanishads, the basic texts of Vedanta, state the non-duality or unity of Brahman and Atman. The four statements indicate the ultimate unity of the individual Atman with God (Brahman). The four Mahāvākyas are:

-

Prajnanam Brahma - "Cons-ciousness is Brahman". (Aitareya Upanishad 3.3 of the Rig Veda)

- Ayam Atma Brahma - "This Self (Atman) is Brahman". (Mandukya Upanishad 1.2 of the Atharva Veda)

- Tat Tvam Asi - "Thou art That". (Chandogya Upanishad 6.8.7 of the Sama Veda)

- Aham Brahmasmi - "I am Brahman". (Brhadaranyaka Upanishad 1.4.10 of the Yajur Veda)

These sayings encapsulate the central truth of Vedant. Each of the Mahavakyas gives a different perspective of the same underlying Reality. All of them, in one way or another, indicate the unity or non-duality of the individual soul (Ataman) with Brahman. It is like gaining different points of view from different viewing points. Together, they converge in a complete understanding: Brahman is the Absolute Reality, Cosmic Consciousness, the fundamental God-stuff from which all divinities and all worlds arise.

Upanishads and the mahavakyas assert that each human being, in his or her innermost self, is this ultimate transcendent God-Reality. It is through practices like yoga and meditation that the individual can realize his or her unity with the Divine and escape the cycle of birth and death in this world.

The first mahavakya, “Consciou-sness is Brahman”, explains the true nature of Brahman. The second mahavakya, “This Self [Atman] is Brahman”, is the self assessment from the seeker when he/she recognizes his/her true divine nature. In the third mahavakya, “Thou art That”, the realized teacher informs the student that "You are that Supreme Brahman". The last mahavakya, “I am Brahman”, is the statement of practice for the seeker to discover the Oneness (non-duality) of Atman and the Brahman.

Prajnanam Brahma (Cons-ciousness is Brahman)

The first Mahavakya, ‘Prajnanam Brahma’, is taken from, Aitareya Upanishad, 3.3 in the Rig Veda. It means that Brahman is pure Consciousness. It is because of this consciousness that all creatures are able to see, hear, smell, speak, and distinguish different tastes. The same consciousness enlivens gods, men, and all other creatures. This consciousness is Brahman.

The word brahman comes form the sanskrit root brh which means knowledge, expansion, and all-pervasiveness. Brahman is used to indicate the infinite, all pervading, non-dual reality. Nothing can exist without consciousness. In absence of consciousness, there is no observer. In absence of the observer, there can be no observed, since it would not be observed even if it existed. Therefore, without consciousness nothing exists, which leads to the conclusion that everything exists in consciousness. Therefore, consciousness is all pervading and infinite. That which is infinite is non-dual. Since there cannot be two non dual entities, we conclude that consciousness is Brahman.

Brahman is the absolute reality, that which is eternal, and not subject to death, decay, or decomposition. In English, we speak of omnipresence or oneness. This is the principle of the word Brahman.

However one chooses to hold the word brahman, it is very useful to remember that Brahman is often described as indescribable. For convenience sake, it is said that Brahman is the nature of existence, consciousness, and bliss, though admitting that these words, too, are inadequate.

This mahavakya is often rendered as: Brahman is the supreme knowledge. Prajnanam also means knowledge. There are many types of knowledge one can attain. However, they all stem from, or are a part of a higher knowledge. There is one exception, and that is the absolute knowledge, which is the highest. It is called “absolute” because it is not stemming from something else. Supreme knowledge is the ground out of which the diversity of knowledge and experience grows. Brahman is the supreme knowledge. Knowing the absolute reality is the supreme knowledge.

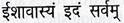

One may also choose to think of Brahman in theological terms, though that is not necessary. Within that perspective, the scholars speak of two principles: immanence and transcendence. Immanence is described as the divinity existing in, and extending into all parts of the created world. In that sense, the mahavakya can be read as suggesting there is no object that does not contain, or is not part of that creation. Ishopanshid (Yajur Veda, Chapter 40, Hymn 1) says:

[Ishavasyam idam sarvam]

[Ishavasyam idam sarvam]

Divine consciousness permeates

all matters in the universe.

Ayam Atma Brahman (This Self (Ataman) is Brahman)

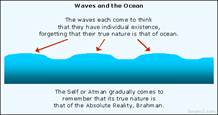

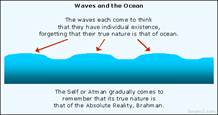

The concept of Ayam Atma Brahman is explained as Atman and Brahman being the same. It portrays the idea that the individual self is one and the same with the Absolute. The concept is often explained with the example of wave and ocean. The aspirant can clearly understand this mahavakya by watching the vastness of the ocean. If a big wave starts to come ashore, and one concentrates on one wave, he can intently notice that the wave gets absorbed in the crashing of the surf, and he can feel the salt spray. In that moment, the person is only aware of the vastness of this one wave. The ocean itself is forgotten during that time. The only idea then prevails is that the ocean and the wave is one and the same.

Atman refers to that pure, perfect, eternal spark of consciousness that is the deepest, central core of human being, while Brahman refers to the oneness of the real and unreal universe. It is like saying that atman is a wave, and brahman is the ocean. The insight of Ayam atma brahma is that the wave and the ocean are one and the same.

Atman refers to that pure, perfect, eternal spark of consciousness that is the deepest, central core of human being, while Brahman refers to the oneness of the real and unreal universe. It is like saying that atman is a wave, and brahman is the ocean. The insight of Ayam atma brahma is that the wave and the ocean are one and the same.

Tat Tvam Asi (Thou art that.)

The third mahavakya is “Tat Tvam Asi” which is variously translated as: "That thou art", or "You are that". It originally occurs in the Chandogya Upanishad 6.8.7, in the dialogue between Uddaalaka and his son Śvetaketu. It appears at the end of a section, and is repeated at the end of the subsequent sections as a refrain.

This mahavakya is stated as if one person is speaking to the other, in a direct speech. The person speaking in this mahavakya is the teacher and the person being spoken to is considered as the student. When the teacher has explained to the students all of the mahavakyas, that the student has already reflected on, and that the student has started to gain some sense of the meaning of the oneness called Brahman, the teacher (Guru) explains to his student that Brahman is that oneness, who resides at the deepest level of one’s being.

Most people accept the identity of the roles in their work area or in their families, such as father or mother, sister or brother, son or daughter. Sometimes, eventually, the common people believe that who they are, is their personality character that have developed through their way of living. If the common men forget their true nature, they come underneath all of the relative identities. The laymen continue their duties, holding identities loosely.

The realization of this mahavakya, “Tat tvam asi”, leads the seekers to see that the relative identities are not who they actually represent. It does not mean that people drop their duties in the world, or stop acting in service of other people because of this realization. Rather, with time, they become more liberal to hold those identities loosely, while increasingly being able to act in the loving service of others, independent of attachment to the innate transitory identities.

Aham brahmasmi (I am Brahman)

This mahavakya occurs in Brihadaranyaka Upanishad, 1.4.10, of the Yajur Veda. Earlier, it was stated that Brahman is consciousness. Here it is clearly stated that “I am Brahman”, that is, “I am consciousness”. This utterly shatters all false identifications in the form of “I am the body”, “I am the mind”, “I am the intellect”, etc. It establishes that I am the consciousness behind all the experiences of the body, mind, and intellect. I am observer; the body, mind, intellect, senses, etc., are only my instruments. I am infinite, I am all pervading.

If carefully examined, this statement destroys all sorrow. Sorrow stems form wanting something, from not having something, a desire frustrated, an expectation let down. Now if I am the infinite, non-dual Brahman, then nothing exists other than me. Therefore, there is no question of desire. I can only desire something other than me. I can only have expectations when there is something other than me to expect something from. Thus this statement removes all sorrows at the root, establishing the identity of myself as Brahman alone.

The concept is often expounded using the metaphor of gold and a gold bracelet, or, clay and the pot. Imagine two possibilities of what a gold bracelet might say if it could speak. It might say:

-

I am a bracelet.

- I am gold.

Which is truer, more everlasting? We might be tempted to say that the statement 1 is more accurate, in that bracelet seems more encompassing, being both bracelet and gold at the same time. However, the bracelet aspect is not eternal. It is temporary. It is only a matter of the particular shape in which the gold was molded.

On the other hand, the statement 2, that "I am gold", is always true, even when the bracelet is melted down or converted to a different piece of jewelry or something else.

Realization of Mahavakyas

Note that the assertion or the statement "I am Brahman” is an internal experience compared to the statement, "The Brahman alone is real" (which sounds like the Brahman over there). The two insights are separate, though they also come to the same conclusion.

It is very different to realize, in direct experience, "I am Brahman!" than one of the statements such as, "Brahman alone is real."

-

Out there: "Brahman alone is real!" seems to be about the world out there. It is a valid perspective.

- In here: "I am Brahman!" is an inner declaration of who I am, in here. This is also a valid perspective.

The truth of a mahavakya comes as an intuitive flash that is progressively deeper as one meditates and practices. It is not merely an intellectual process, as it might appear to be by explaining the gold metaphor. The metaphors are used as a means of explaining to a point the principle but this is not the end of the process. In a sense, such explanations are only the beginning of the process. The key is in the still silent reflection in the inner workshop of contemplation and yoga meditation.

The initial insights come somewhat like the creative process when you are trying to solve some problem in daily life. You think and think, and then finally let go into silence. Then, suddenly, the creative idea just pops out, giving you the solution to your problem. The contemplation on the mahavakyas is somewhat like that at first. Later, it goes into deeper meditation.

Insight comes within your own context. One may experience himself or herself as being like the gold or the clay, or like a wave in an ocean of bliss, that realizes the wave is also the ocean. With all these metaphors used only as tools of explanation, the insight of each person will come in the context of their own culture and thought process, and will not seem foreign or unnatural.

Other Mahavakyas

It should be noted that, over the time, some scholars have added other statements as mahavakyas. Some of them are:

-

Brahma satyam jagan mithya (Brahman is real; the world is unreal).

- Ekam evadvitiyam brahma (Brahman is one - without a second).

- Sarvam khalvidam brahma (All of this is Brahman).

- Soham (I am Him).

- Ishavasyam idam sarvam (Divine consciousness permeates all matters in the universe).

Please note that all of these statements essentially articulate the same thesis, that is, the non-duality of Ataman with Brahaman.

Source: MARG, Sep-Oct ’09, 5#5, p.9-11.

Marg Foundation, P.O. Box 714. Gaithersburg, MD 20884-0714

Unlike OM, Swastika is not a syllable or a letter, but a pictorial representation in the shape of a cross with branches bent at right angles and facing in a clockwise direction. A must for most religious celebrations and festivals, Swastika symbolizes the eternal nature of the Brahman, for it points in all directions, thus representing the omnipresence of the Absolute.

The term 'Swastika' is a fusion of the two Sanskrit words 'Su' (good) and 'Asati' (to exist), which, when combined, means May good prevail!.

Unlike OM, Swastika is not a syllable or a letter, but a pictorial representation in the shape of a cross with branches bent at right angles and facing in a clockwise direction. A must for most religious celebrations and festivals, Swastika symbolizes the eternal nature of the Brahman, for it points in all directions, thus representing the omnipresence of the Absolute.

The term 'Swastika' is a fusion of the two Sanskrit words 'Su' (good) and 'Asati' (to exist), which, when combined, means May good prevail!.  Light symbolizes knowledge, and darkness, ignorance. The Lord is the "Knowledge Principle" (chaitanya) who is the source, the enlivener and the illuminator of all knowledge. Hence light is worshiped as the Lord himself.

Light symbolizes knowledge, and darkness, ignorance. The Lord is the "Knowledge Principle" (chaitanya) who is the source, the enlivener and the illuminator of all knowledge. Hence light is worshiped as the Lord himself.

The term “rangoli” is made up of two words, rang (color) and avali, meaning row of colors, or creepers of colors. Rangoli is known by different names in different parts of the country:

The term “rangoli” is made up of two words, rang (color) and avali, meaning row of colors, or creepers of colors. Rangoli is known by different names in different parts of the country:

The fire is the great purifier and, in Hindu tradition, all sacrifices are offered to the fire. It stands for the principle of sacrifice. Saffron is also the color of sunrise and sunset. When the day dawns, the rising sun reminds us to wake up, shake off lethargy, and do our duty. The sun burns throughout the day giving life to one and all without demanding anything in return. The sunset teaches us the true principle of giving by serving the society without any expectation.

The fire is the great purifier and, in Hindu tradition, all sacrifices are offered to the fire. It stands for the principle of sacrifice. Saffron is also the color of sunrise and sunset. When the day dawns, the rising sun reminds us to wake up, shake off lethargy, and do our duty. The sun burns throughout the day giving life to one and all without demanding anything in return. The sunset teaches us the true principle of giving by serving the society without any expectation. Hindus use flowers in puja (worship). Though any available flower is auspicious for puja, the most revered and esteemed by God and man is the magnificent lotus.

Hindus use flowers in puja (worship). Though any available flower is auspicious for puja, the most revered and esteemed by God and man is the magnificent lotus. A kalasha is brass, clay, or copper pitcher filled with water. Mango leaves are placed in the mouth of the pot and a coconut is placed over it. A red or white thread is tied around its neck or sometimes all around it in a intricate diamond-shaped pattern. The pot may be decorated with designs, such as swstika. Such a pot is known as a kalasha.

A kalasha is brass, clay, or copper pitcher filled with water. Mango leaves are placed in the mouth of the pot and a coconut is placed over it. A red or white thread is tied around its neck or sometimes all around it in a intricate diamond-shaped pattern. The pot may be decorated with designs, such as swstika. Such a pot is known as a kalasha. The gesture (or mudra) of namaste is a simple act made by bringing together both palms of the hands before the heart, and slightly and gently bowing the head as one says, "Namaste”. In the simplest of terms, it is accepted as a humble greeting straight from the heart and reciprocated accordingly. The hands held in union signify the oneness of an apparently dual cosmos, the bringing together of spirit and matter, or the self meeting the Self. It has been said that the right hand represents the higher nature or that which is divine in us, while the left hand represents the lower, worldly nature.

The gesture (or mudra) of namaste is a simple act made by bringing together both palms of the hands before the heart, and slightly and gently bowing the head as one says, "Namaste”. In the simplest of terms, it is accepted as a humble greeting straight from the heart and reciprocated accordingly. The hands held in union signify the oneness of an apparently dual cosmos, the bringing together of spirit and matter, or the self meeting the Self. It has been said that the right hand represents the higher nature or that which is divine in us, while the left hand represents the lower, worldly nature.

Atman refers to that pure, perfect, eternal spark of consciousness that is the deepest, central core of human being, while Brahman refers to the oneness of the real and unreal universe. It is like saying that atman is a wave, and brahman is the ocean. The insight of Ayam atma brahma is that the wave and the ocean are one and the same.

Atman refers to that pure, perfect, eternal spark of consciousness that is the deepest, central core of human being, while Brahman refers to the oneness of the real and unreal universe. It is like saying that atman is a wave, and brahman is the ocean. The insight of Ayam atma brahma is that the wave and the ocean are one and the same.